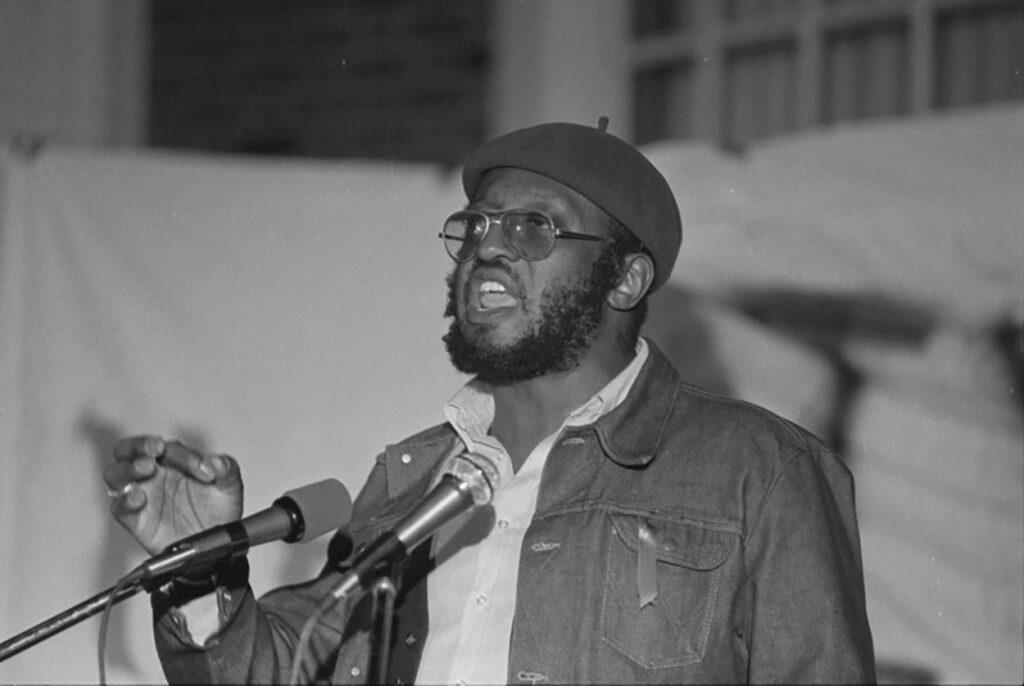

From Mozambique to Brazil, Prexy Nesbitt has made great strides in his pursuit of global peace and conflict resolution.

Written by Mitali Shukla

Fifty-three years ago, on Aug. 5, 1966, Rozell “Prexy” Nesbitt acted as Martin Luther King Jr.’s bodyguard during the violent march in Marquette Park, Illinois.

“We had a good relationship. Marquette Park in Chicago was the march he said he faced the most violence – even than in the South,” Nesbitt told The Panther. “On that march, I missed a brick that hit him in the head. He went down bleeding, but he was still big enough to get up and say, ‘Prexy, I thought you were this great football player.’ That was the kind of person he was.”

Today, Nesbitt, who has led efforts against stratification globally – from South Africa to Brazil – is a presidential fellow and guest professor at Chapman. He was born in the west side of Chicago, Illinois.

“It was a mixed bag because I grew up with all my cousins, all around like siblings,” Nesbitt said. “But there were also a lot of challenging, difficult situations because of how segregated and racist Chicago was.”

Some of those difficult situations he described were having very little money, though he and his extended family were able to make ends meet. He later attended Antioch College in 1963. Nesbitt said that during his time in Yellow Springs, Ohio, in conjunction with Antioch’s Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), the university sent more civil rights activists to the South than any other college.

“My mother wouldn’t let me go because she was convinced that I would be killed,” he said. “I don’t think there was any college – especially of its size – that could match it for getting people involved.”

Nesbitt spent a part of his college career studying abroad in Tanzania, where he attended the University of Dar es Salaam as the school’s first international student. While he was there he befriended three Ismaili women who inspired him travel to South Africa after his graduation in 1967, where he focused on ending Apartheid.

“It’s been extremely difficult. (South Africa) remains one of the most unequal societies in the world,” he said. “But the people who died for a new South Africa did not do so in vain.”

Junior peace studies and psychology double major and one of the presidents of the peace studies union, Sophia Morissette, is enrolled in Nesbitt’s “Model United Nations I” course and recounts his stories from lecture.

“He told us this amazing story about how he had to be smuggled in and out of South Africa with a priest,” Morissette said.

Following his work with Nelson Mandela – as they were companions in ending Apartheid – Nesbitt recalled an exchange between Mandela and talk show host Oprah when he was on her show.

“Oprah said, ‘Nelson, I love you; you’re my greatest hero,’ and he would always say, ‘I’m not alone. I’m just one member of the African National Congress,’” Nesbitt said. “He’d say, ‘It is people who do things, not the leaders,’ all the time.”

Prior to marching in Marquette Park, Martin Luther King Jr. spoke in Memorial Hall on Dec. 10, 1961; during which Nesbitt was still in South Africa. After all the time Nesbitt spent challenging unequal cultural opportunities and status-quos, he said he found himself at Chapman through a connection to the university – which came from Don Will, the founder of the peace studies department who passed away in February 2014.

“My dearest friend was Don Will,” he said. “I was the best man at his wedding and I am the godfather of his son.”

He visited Chapman between 10 and 12 times prior to his employment, and has a network of friends among the faculty are here. He now works as a guest professor in the peace studies department. Breil Bonaguro, a junior peace studies major, said she was inspired by Nesbitt’s outstanding achievements.

“All the things he has been involved with is extremely inspiring because we talk about the civil rights movement and we talk about Apartheid movements – but to speak with someone who was actually there is so impactful,” Bonaguro said.

Bonaguro looks to Nesbitt as an inspirational figure while she pursues her peace studies degree. She intends to use it to teach in developing countries all over the world.

“He was an ambassador at Mozambique, doing things that a lot of peace studies majors would love to do,” she said.

Akin to Bonaguro’s aspirations, Nesbitt mentioned the recent efforts of climate activist Greta Thunberg, who went viral when she gave her speech to world leaders at the United Nations Climate Action Summit. Thunberg rallied people globally to fight for reducing humanity’s carbon footprint.

“I loved it; it was just fantastic. It reminded me very much of what it was like working with Dr. King and Nelson Mandela,” Nesbitt said. “They are leaders who encourage you by leading you with their example. It’s incredible that they’re being led by this 16-year-old girl from Sweden.”

In terms of on-campus advocacy, Morissette and the Model United Nations class attended a La Frontera event which was organized by the peace studies department.

“Instead of having class one week, we all ventured to one of the La Frontera events to see a screening of a movie about the Holocaust,” Morissette said. “We had a great discussion after.”

When asked about the Patriot Front activity on campus, Nesbitt rolled his eyes and told The Panther that the organization’s actions were cowardly.

“They refuse to be out front and represent their views to people so you can confront them and examine them and they represent a very backwards philosophy at odds with the flow of world history,” he said. “It is asserting that they are right by virtue of their color. White nationalists say that is what matters.”

In light of the posters and stickers scattered throughout campus, Nesbitt added that Chapman has a responsibility to recruit more students and faculty of color, all while proudly doing so.

“Chapman has to turn this around and proudly turn it around,” he said. “That is the thrust of history and that is where the world is moving. Chapman has to get with the world.”